Georges SEURAT. Poseuses. 200 X 251. 1886-1888. Merion, Fondation Barnes

Georges SEURAT.

Une Baignade (Asnières). 1883-1884. 200 X 300. Londres, National Gallery

Georges SEURAT.

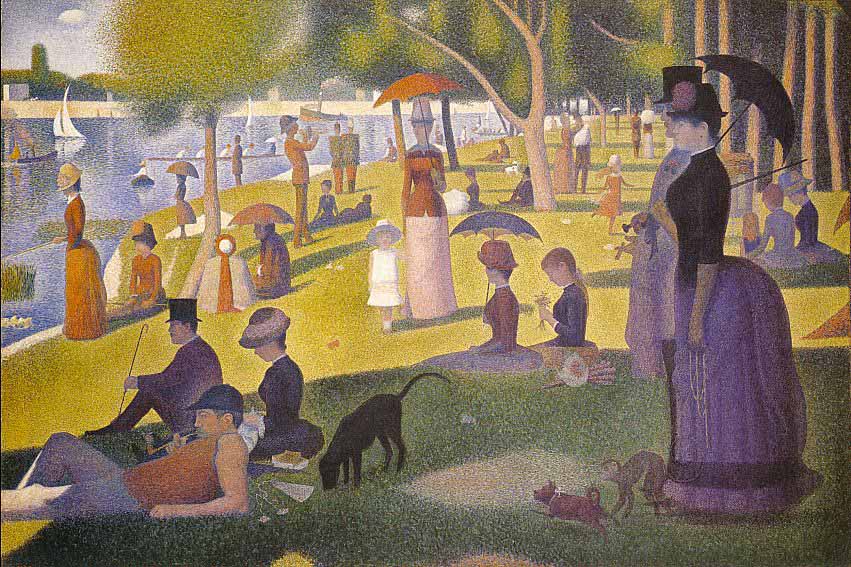

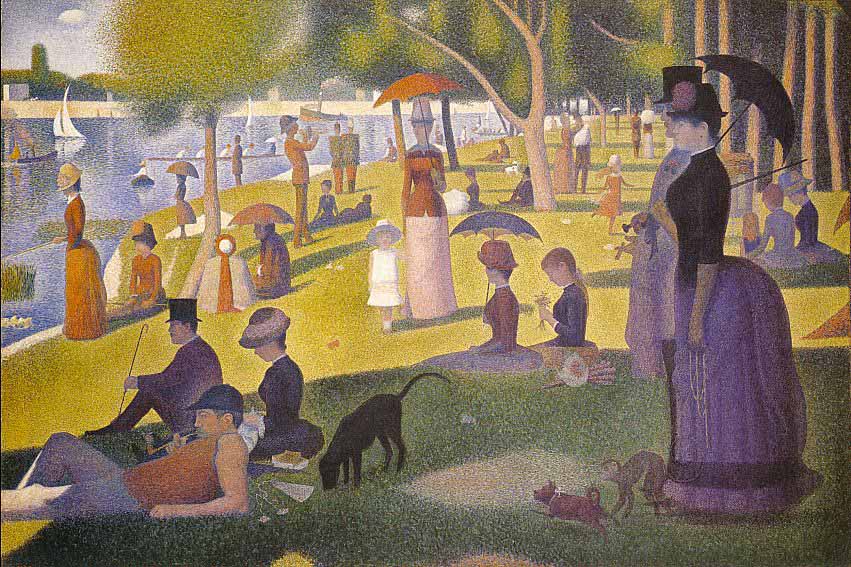

Un Dimanche après-midi à la Grande-Jatte. 1884-1886. 225 X 340. Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago

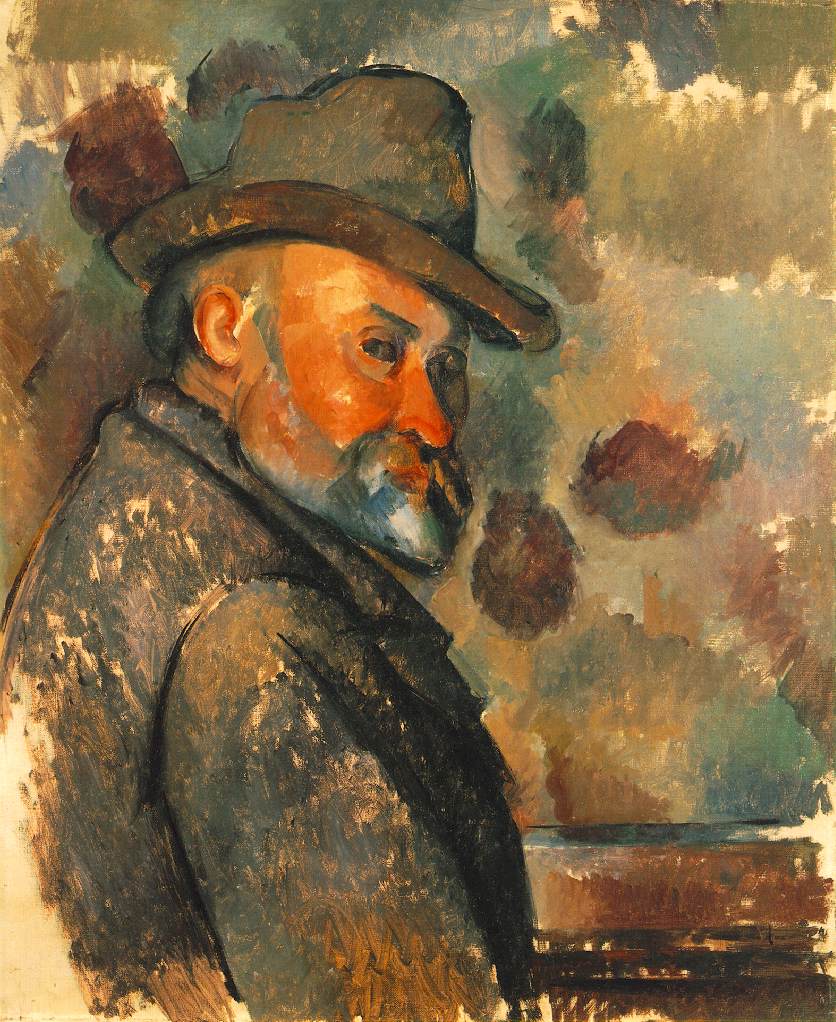

Un mort. Né et décédé à Paris : 2 Décembre 1859-29 Mars 1891. Quatre ans élève à l'école des Beaux-Arts sous Henri Lehmann. Début, en 1883, au Salon officiel du Palais de l'Industrie : un portrait au crayon, grandeur naturelle, de son très ami Aman Jean, par le livret cocassement intitulé Broderie, titre exact d'un autre crayon, refusé. Au baraquement de la rue des Tuileries, le 25 Mai 1884, grande toile, Une Baignade (Asnières). À la huitième exposition des Impressionnistes, rue Laffitte no 1, 15 Mai 1886, neuf peintures ou dessins et, enfin, soixante, exhibés aux sept manifestations de la Société des Artistes Indépendants, du 10 Décembre 1884 au 20 Mars 1891. Parmi quoi : Un Dimanche à la Grande-Jatte, Poseuses, Chahut, Cirque, où cinquante hommes ou femmes se promènent, s'étendent, posent, dansent, contemplent assis, applaudissent, rient, courent, s'élancent à cheval, sillonnent l'espace, extraient des sons — avec sérénité, dans la lumière jaune. (Peints dans leur réelle dimension).

Ce chromatiste wagnérien avait un idéal : l'Harmonie. L'Art, pour lui, c'était l'Harmonie, et l'Harmonie, l'analogie des contraires, l'analogie des semblables — de ton, de teinte, de ligne. Comme moyen d'expression de cette technique : le mélange optique des tons, des teintes et de leurs réactions (ombres) suivant des lois très fixes. Et Georges Seurat fut le véritable initiateur de la division du ton, il le faut redire. A sa dernière exposition, nouvelle innovation, il avait substitué au cadre blanc ou neutre le cadre peint, opposé aux tons, teintes et lignes du motif.

Comme Maximilien Robespierre, Georges Seurat croyait à ce qu'il disait (rarement), donc à ce qu'il exécutait. Il était silencieux, obstiné et pur. De même qu'il conférait aux êtres une austérité hiératique, il attribuait à la Nature le calme endormeur de l'extase et c'est ainsi qu'il peignit des paysages de la BasseNormandie, de la Picardie, de la Seine.

Une stupide et subite maladie l'emportait en quelques heures, au milieu du triomphe (...)

Jules CHRISTOPHE. « Chromo-luminarisme : Georges Seurat ». La Plume, 1er septembre 1891

Georges Seurat suivit les cours de l'école des Beaux-Arts ; mais son intelligence, sa volonté, son esprit méthodique et clair, son goût si pur et son œil de peintre le gardèrent de l'influence déprimante de l'École. Fréquentant assidûment les musées, feuilletant dans les bibliothèques les livres d'art et les gravures, il puisait dans l'étude des maîtres classiques la force de résister à l'enseignement des professeurs. Au cours de ces études, il constata que ce sont, des lois analogues qui régissent la ligne, le clair-obscur, la couleur, la composition, tant chez Rubens que chez Raphaël, chez Michel-Ange que chez Delacroix : le rythme, la mesure et le contraste.La tradition orientale, les écrits de Chevreul, de Charles Blanc, de Humbert de Superville, d'O. N. Rood, de H. Helmholtz le renseignèrent. Il analysa longuement l'œuvre de Delacroix, y retrouva facilement l'application des lois traditionnelles, tant dans la couleur que dans la ligne, et vit nettement ce qui restait encore à faire pour réaliser les progrès que le maître romantique avait entrevus.

Le résultat des études de Seurat fut sa judicieuse et fertile théorie du contraste, à laquelle il soumit dès lors toutes ses œuvres. Il l'appliqua d'abord au clair-obscur : avec ces simples ressources, le blanc d'une feuille de papier Ingres et le noir d'un crayon Conté, savamment dégradé ou contrasté, il exécuta quelque quatre cents dessins, les plus beaux dessins de peintre qui soient. Grâce à la science parfaite des valeurs, on peut dire que ces blanc et noir sont plus lumineux et plus colorés que maintes peintures. Puis, s'étant ainsi rendu maître du contraste de ton, il traita la teinte dans le même esprit et, dès 1882, il appliquait à la couleur les lois du contraste et peignait avec des éléments séparés — en employant des teintes rabattues, il est vrai — sans avoir été influencé par les impressionnistes dont, à cette époque, il ignorait même l'existence.

[...]

En 1884, à la première exposition du groupe des Artistes Indépendants, au baraquement des Tuileries, Seurat et Signac, qui ne se connaissaient pas, se rencontrèrent, Seurat exposait sa Baignade, refusée au Salon de cette même année. Ce tableau était peint à grandes touches plates, balayées les unes sur les autres et, issues d'une palette composée, comme celle de Delacroix, de couleurs pures et de couleurs terreuses. De par ces ocres et ces terres, le tableau était terni et paraissait, moins brillant que ceux que peignaient les impressionnistes avec leur palette réduite aux couleurs du prisme. Mais l'observation des lois du contrasle, la séparation méthodique des éléments — lumière, ombre, couleur locale, réactions —, leur juste proportion et leur équilibre conféraientt à cette toile une parfaite harmonie.

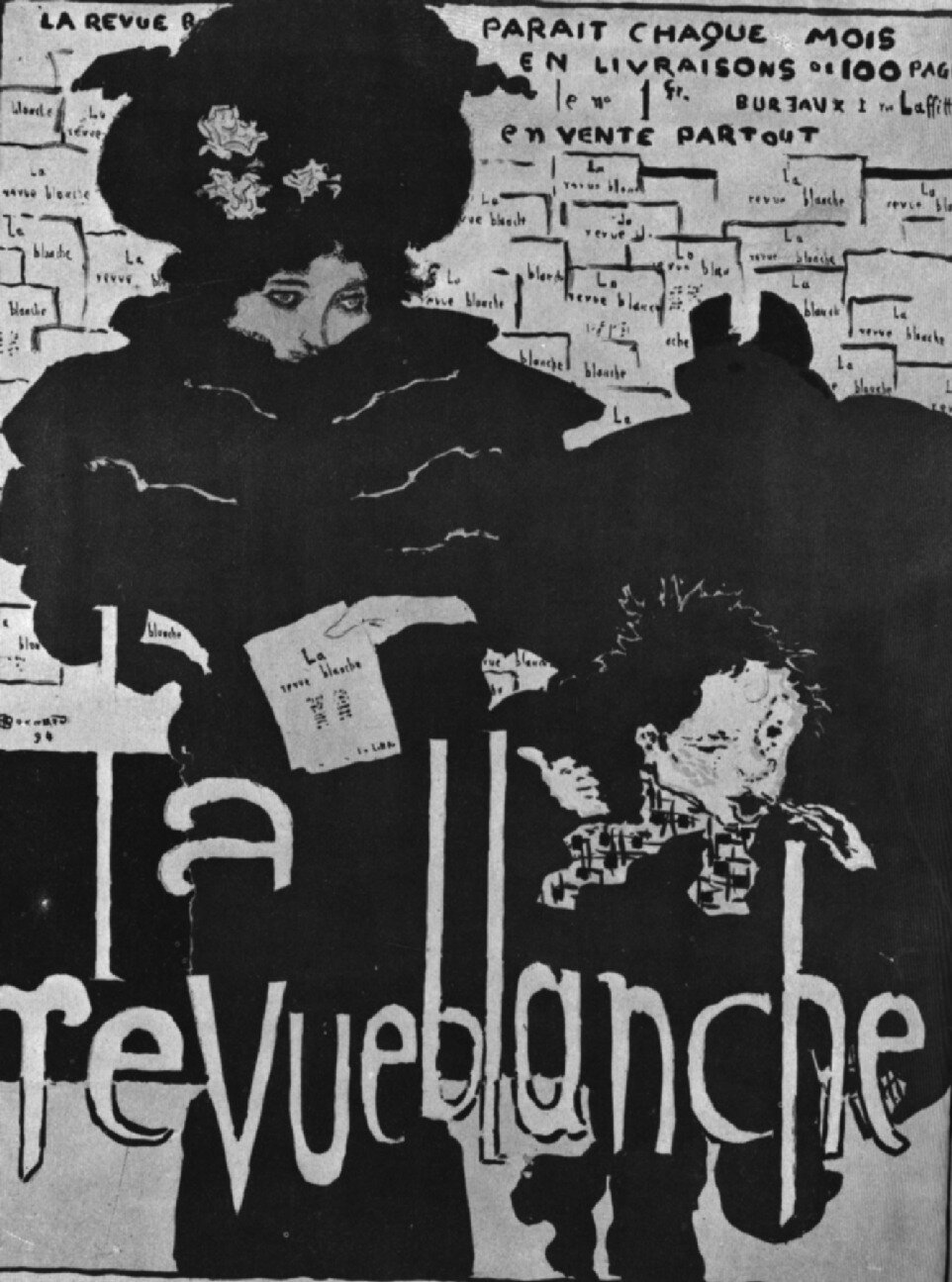

Paul SIGNAC. « D'Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionnisme ». La Revue Blanche, 1899

Georges SEURAT.

La Tour Eiffel. 1889. 24 X 15. San Francisco, The Fine Art Museum

Le Néo-Impressionniste ne pointille pas, mais divise.

Or diviser c'est :

S'assurer tous les bénéfices de la luminosité, de la coloration et de l'harmonie par :

1° Le mélange optique de pigments uniquement purs (toutes les teintes du prisme et tous les tons) ;

2° La séparation des divers éléments (couleurs locale, couleur d'éclairage, leurs réactions, etc.) ;

3° L'équilibre de ces éléments et de leur proportion (selon les lois du contraste, de la dégradation et de l'irradation) ;

4° Le choix d'une touche proportionnée à la dimension du tableau.

Paul SIGNAC. « D'Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionnisme ». La Revue Blanche, 1899

Georges SEURAT.

Le Chahut. 1889-1890. 169 X 139. Otterlo, Musée Kröller-Müller

Admirers of Seurat often regret his method, the little dots. Imagine, Renoir said, Veronese's Marriage at Cana done in petit point. I cannot imagine it, but neither can I imagine Seurat's pictures painted in broad or blended strokes. Like his choice of tones, Seurat's technique is intensely personal. But the dots are not simply a technique; they are a tangible surface and the ground of important qualities, including his finesse. Too much has been written, and often incorrectly, about the scientific nature of the dots. The question whether they make a picture more or less luminous hardly matters. A painting can be luminous and artistically dull, or low-keyed in color and radiant to the mind. Besides, bow to paint brightly is no secret requiring a special knowledge of science. Like Van Gogh, Seurat could have used strong colors in big areas for a brighter effect. But without his peculiar means we would not have the marvelous delicacy of tone, the uncountable variations within a narrow range, the vibrancy and soft luster, which make his canvases, and especially his landscapes, a joy to contemplate. Nor would we have his surprising image-world where the continuous form is built up from the discrete, and the solid masses emerge from an endless scattering of fine points - a mystery of the coming-into-being for the eye. The dots in Seurat's paintings have something of the quality of the black grains in his incomparable drawings in conte crayon where the varying density of the grains determines the gradations of tone. This span from the tiny to the large is only one of the many striking polarities in his art.

If his technique depends on his reading of science, it is no more scientific than the methods of flat painting; it is surely not better adapted to Seurat's end than was the technique of a good Egyptian painter to his own special goals. Yet was Seurat's aim simply to reproduce the visual impression by more faithful means? Certain phrases in his theoretical testament - a compact statement of two pages - might lead us to think so; but some passages that speak of harmony and contrast (not to mention the works themselves) tell us otherwise. He was interested, of course, in his sensations and the means of rendering them, as artists of the Renaissance were passionately interested in perspective. When used inventively, perspective had also a constructive and expressive sense. In a similar way, Seurat's dots are a refined device which belongs to art as much as to sensation - the visual world is not perceived as a mosaic of colored points, but this artificial micro-pattern serves the painter as a means of order portioning and nuancing sensation beyond the familiar qualities of the objects that the colors evoke. Here one recalls Rimbaud's avowal in his Alchemy of the Word : « I regulated the form and the movement of each consonant », which was to inspire in the poets of Seurat's generation a similar search of the smallest units of poetic effect.Seurat's dots may be seen as a kind of collage. They create a hollow space within the frame, often a vast depth; but they compel us also to see the picture as a finely structured surface made up of an infinite number of superposed units attached to the canvas. When painters in our century had ceased to concern themselves with the rendering of sensations - a profoundly interesting content for art - they were charmed by Seurat's inimitable dots and introduced them into their freer painting as a motif, usually among opposed elements of structure and surface. In doing so, they transformed Seurat's dots - one can't mistake theirs for his - but they also paid homage to Seurat.

Seurat's dots, I have intimated, are a means of creating a special kind of order. They are his tangible and ever-present unit of measure. Through the difference in color alone, these almost uniform particles of the painter modulate and integrate molar forms; varying densities in the distribution of light and dark dots generate the boundaries that define figures, buildings, and the edges of land, sea and sky. A passionate striving for unity and simplicity together with the utmost fullness appears in this laborious method which has been compared with the mechanical process of the photo-engraved screen. But is it, in the hands of this fanatical painter, more laborious than the traditional method with prepared grounds, fixed outlines, studied light and shade, and careful glazing of tone upon tone ? Does one reproach Chardin for the patient work that went into the mysterious complex grain of his little pictures ? Seurat practices an alchemy no more exacting than that of his great forebears, though strange in the age of Impressionist spontaneity. But his method is perfectly legible; all is on the surface, with no sauce or secret preparations; his touch is completely candid, without that "infernal facility of the brush" deplored by Delacroix. It approaches the impersonal but remains in its frankness a personal touch. Seurat's hand has what all virtuosity claims : certitude, rightness with least effort. It is never mechanical, in spite of what many have said - I cannot believe that an observer who finds Seurat's touch mechanical has looked closely at the pictures. In those later works where the dots are smallest, you will still discover clear differences in size and thickness; there are some large strokes among them and even drawn lines. Sometimes the dots are directionless, but in the same picture you will observe a drift of little marks accenting an edge.

With all its air of simplicity and stylization, Seurat's art is extremely complex. He painted large canvases not to assert himself nor to insist on the power of a single idea, but to develop an image emulating the fullness of nature. One can enjoy in the Grande Jatte many pictures each of which is a world in itself ; every segment contains surprising inventions in the large shapes and the small, in the grouping and linking of parts, down to the patterning of the dots. The richness of Seurat lies not only in the variety of forms, but in the unexpected range of qualities and content within the same work : from the articulated and formed to its ground in the relatively homogeneous dots ; an austere construction, yet so much of nature and human life; the cool observer, occupied with his abstruse problems of art, and the common world of the crowds and amusements of Paris with its whimsical, even comic, elements; the exact mind, fanatic about its methods and theories, and the poetic visionary absorbed in contemplating the mysterious light and shadow of a transfigured domain. In this last quality - supreme in his drawings - he is like no other artist so much as Redon. Here Seurat is the visionary of the seen as Redon is the visionary of the hermetic imagination and the dream.

Seurat's art is an astonishing achievement for so young a painter. At thirty-one - Seurat's age when he died in 1891 - Degas and Cézanne had not shown their measure. But Seurat was a complete artist at twenty-five when be painted the Grande Jatte. What is remarkable, beside the perfection of this enormously complex work, is the historical accomplishment. It resolved a crisis in painting and opened the way to new possibilities. Seurat built upon a dying classic tradition and upon the Impressionists, then caught in an impasse and already doubting themselves. His solution, marked by another temperament and method, is parallel to Cézanne's work of the same time, though probably independent. If one can isolate a single major influence on the art of the important younger painters in Paris in the later '80s, it is the work of Seurat ; Van Gogh, Gauguin and Lautrec were all affected by it.

Meyer SCHAPIRO. Modern Art, Nineteenth and Twentieth Century. 1978

Georges SEURAT. Poseuses. 200 X 251. 1886-1888. Merion, Fondation Barnes

Georges SEURAT. Poseuses. 200 X 251. 1886-1888. Merion, Fondation Barnes Georges SEURAT. Un Dimanche après-midi à la Grande-Jatte. 1884-1886. 225 X 340. Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago

Georges SEURAT. Un Dimanche après-midi à la Grande-Jatte. 1884-1886. 225 X 340. Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago